If you would like more than 8 samples, please contact a trader directly.

Cart

A trader will contact you with shipping and payment options after checkout. Please note: free samples are provided to commercial roasting businesses only.

It took three people and a bull mastiff two hours and nine calls to find the spot. The dead-end responses ranged from an honest – ‘huh’ – to the confused – ‘you’re crazy’, with a few lazier warnings of ‘it’s too dangerous’ in there as well. But we finally found one who didn’t hang up – the call just dropped. So we sent a text and told them we were on our way.

At the gate we were asked for money before entering – they didn’t think we were serious. We were asked if we knew what we were doing, if we were sure we wanted to go through with this. Then we were asked what we wanted for dinner.

Spooky. But the spot was perfect, and worth the effort. An exposed hilltop from where we could see the lights of Nairobi in one direction, and the silhouette of Kilimanjaro in the other. The line of sight was so good, I was told, that back in the World War the Brits set up pillboxes here – three AA guns to shoot down Italian planes coming in from Ethiopia.

The place looked the part, or at least, like it had played a part in some seventy-five year old history … and that maybe no one has cared for it since. We had two in our group walk past the barking dog we never saw but only heard, and into the guest quarters – then right back out and to the closest hotel. They weren’t into camping, and I don’t blame them for not staying inside. It was a beautiful plantation house cut in the classic style. Only thing is that it reeked of taxidermy, had mattresses pushed up against the wall to act as insulation, and was so completely yellowed that only the boldest of mold stains stood out.

That was inside, but outside the hilltop hid a private waterfall that cut between and then down the slopes of two tea estates. Tea, you may know, tends to glow an iridescent green with morning and evening sun, making this already majestic waterfall into something even more.

There was beer (Tusker, even though I prefer me a White Cap), food (Indian with Chapati), and a fire (with our very own Masai guard to keep us company). Plus, we were only forty minutes from our meeting that evening – while this place was far from normal, it was close to perfect.

Turns out, in Kenya, camping isn’t so normal, which is why we were the weirdos. While hunting down equipment to rent I was even asked, twice, ‘are you camping …recreationally?’.

Well, yes, of course we were camping recreationally. But I also had some business in mind. We set out from Nairobi to spend a couple of nights at two farms – meetings are more fun when they can go into the night.

One night saw a BBQ with our friends in Giakanja. In the States a BBQ may mean pork, beef or chicken depending on where you from. There BBQ is called Nyama Choma, and it’s all goat. And all of the goat. I’d asked for vegetarian options for our vegetarian friends … they got a fish.

The meeting started with feedback on Giakanja’s coffee, and introductions to their customers. It was a success story; last year saw record prices, qualities and group engagement. We reported a desire to double our purchasing, brought a contract to show our commitment, and then of course there was the goat to help us celebrate.

The inevitable question came up during the meeting – not a question, really, but an ask. No matter the price, it’s reasonable for farmers to want more money. In this case the question came up with interesting effect.

“So, you will pay a higher price this year, right”?

To start, I felt that we needed to manage down expectations. So I asked what price they’d received last year – a healthy $4.00 / pound for an AB grade – and if they were happy with this. Yes, of course they were –last year saw record prices. Good, I responded, ‘we have contracted to buy twice as much as last year, if you can match the same quality’. My colleagues thought me crazy, I told him, for saying I’d buy such an expensive coffee before even knowing what it would taste like.

Which was a good segue to recap the rules of the game. Roasters buy on quality, that when a sale is made it’s because of the effort they put into quality. So – in reality –the work a farmer does in the field does much to dictate price. In other words, the better the farming the better the quality, the better the quality the better the price. So he’s got both stake and say in the matter.

Next, I wanted to add some context. So I asked the group who knew about the International Price of coffee – not one raised a hand. Then I asked every U.S. roaster in the group ‘what is the most expensive coffee on your menu’. To a person, luckily for me, each of them said ‘my Kenyan’.

| 2018 | Avg Auction | Highest Auction |

| AA | $ 3.31 | $ 5.53 |

| AB | $ 2.54 | $ 3.99 |

| PB | $ 2.37 | $ 3.92 |

| C | $ 1.92 | $ 2.66 |

Average auction prices are drawn across three random auctions in 2018 at a time when NYBOT was avg 1.23. Auction prices are quoted converted into USD / lb, but remain FOT Nairobi. Note that highest auction prices are more indicative of direct trade prices than averages, which include lower grades.

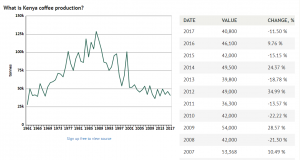

Kenyan coffee is already at the top of the value-chain, neither prices nor quality could get much higher. Even while farmers the world round freeze in sub-dollar coffee prices, Kenyans enjoy a plump cushion from quality premiums. And despite all this, coffee in Kenya is on the decline. In fact, this is the only place we work which produces less coffee every year.

And this is why, to the farmer who asked for a higher price, I ultimately said “the best way to make more money from coffee … is to plant more coffee”. This felt like a risk, and I was surprised to see nods and soft applause.

To understand why I was surprised to find support we must first think about the mentality of working in a shrinking industry. Every year there is less coffee than the year before. That means every year other farmers you know are getting out of coffee.

Before we count it off as lazy or crazy let’s puzzle through the more interesting ‘why’. With world-class quality and top of the line prices, why are farmers getting out of coffee?

Space is one answer; coffee shares the highlands with an ever-expanding Nairobi, which turns the country’s oldest coffee estates into its newest shopping malls. With real estate prices what they are in Nairobi, and with Nairobi growing as fast as it is – you’d be crazy not to sell at some point.

But space is only part of the answer – following the rest will take us to the fourth dimension.

Money is worth more now than it is later – this idea probably referred to by Wikipedia as the ‘time value of money’. It banks on being able to invest money you have now, allowing you to earn interest, and making it worth more than money you don’t have now, which can’t be put to work.

Coffee is the king of cash crops in Kenya, but it is losing to development, to tea, to pumpkins, nuts and corn for dairy. In fact, as a crop, it is the loser – coffee hasn’t been cool in Kenya since 1986.

To start, it’s hard. It takes time, a lot more time than other crops where you can ‘scratch the earth, wait a few months, and then pick your food’. Kenyan coffee is so good because they take time to cultivate it – that’s a 12-month job! And it takes time to navigate the heavily regulated system that touches (and taxes) nearly every point of coffee production. And, most importantly, with coffee it takes time to get paid.

Nearly everything else a farmer can do in Kenya pays at least monthly. Monthly is good, it’s regular. You can see it, eat it, use it. Kenya is developing so fast that you need money now to afford your house tomorrow.

Coffee, however, is annual, and difficult to plan around. Sure, coffee money is good money, but discounted by doubts on ‘how much are we talking about’ and ‘when will I get paid’. Questions I’d ask myself if I was being asked to do more work.

Turns out that these questions do have answers – we found some clues on our other overnight visit – an attempt to stay at the famous combined Yara Estate and Windrush Farms. Well, we failed, bringing us to the creepy beautiful hilltop that started this story. But it did allow our meeting to continue late into the night, where we failed to get what we wanted out of their farm manager Edward … but still ended up with a more than we expected.

By that I mean that we failed to get any commitment to lot separation or processing improvement – and that was one of my goals for the meeting. Kenyan farmers are conservative, preferring the way their parents processed coffee.

With the quality they’re putting out I’m not one to argue … but I would really love to taste the difference between of Yara’s 12 blocks. Or to see what percent would be floated out if they tried floated before pulping. Or maybe just take a quick measure of the heat in the drum used to skin dry fresh parchment. Or, you know, buy this massive enterprise a moisture meter so that they know when coffee was done on the drying bed.

That said, they are averaging 15 days of drying, and producing primo coffees, so maybe sticking to best practices allows you to cut a few corners here and there.

If it’s not broken don’t fix it, so says Edward, who balked at any change to S.O.P.

So we didn’t get much out of him in terms of experimentation, separation or special preparation – but we are still discussing, and hope to come to some bite-sized compromise soon.

As additional consolidation, we also got from him the story of Gatatha Farmers Cooperative, including the secret to their success.

The Gatatha Farmers Cooperative annual board meeting is in February. Four years ago the discussion was about coffee. Production was down, currencies were crazy. Maybe it was time to get out.

Gatatha is a fifty-year old union with over three thousand members. All it takes is one vocal member to suggest that they sell roadside land for development, that they convert one field of coffee to tea, or to sell-back their shares – and the entire coop can start to crumble away from coffee.

That’s what’s happened to most of Kenya’s larger cooperatives. Market volatility, local and national political, pressure from members for fast money – these claim coop after coop, leaving few coffee-focused shops standing.

But Gatatha is standing strong, growing even. Their secret lies in the fourth dimension.

Sure, they say, coffee is annual. And our members want regular monthly income. Easy enough – all you got to do is put your long money towards investments that pay fast money. That’s to say that annual coffee profits are invested into industries which pay regular monthly dividends to members.

This portfolio approach actually keeps the focus on the farms; the more profit, the more that can be invested (including in budgets, bonuses and staff). The more that’s invested, the more you can expect in monthly dividends. So coffee is the core of the portfolio, and the one sure earner.

This is the argument that was likely made that fateful day in February, when Gatatha decided to double down in coffee. Investments go up and down, they must have said, but coffee allows us to make more investments overall, meaning our downs will less low, and our ups will go a lot higher.

So, the decision was made. Edward was brought in as the turn-around man. Since, he’s invested in pruning, mulching, feeding and soil care. Much of Windrush Farms is already organic; his goal is to get to 100% in the next five years. Production is up, and quality seems to be too. The state of the core is strong.

Their 2019 board meeting happened right after we left, and I’m not sure what was discussed. But I do know that our 2018 sales report was presented to members of the board, and this makes me proud. It has a full physical and sensorial analysis of their coffee, a record of past and planned purchases, a map of where their samples we sent, and a list of their top customers. But more, Edward told me, this was the first feedback they’ve received from customers of their coffee – and consequentially – the first time that quality was expressed in anyway other than outturn at the mill or price at auction.

If good graces hold then maybe, just maybe we can get them to at least separate lots by block. They’d learn a lot, maximize earnings, build new brands and still always have the option to blend it all back together like they do now.

With all they have to gain and how little it’d cost to do – they’d be crazy not to. But when I’d made this argument before Edward had responded ‘if it’s not broken I’d be crazy to fix it’.

Hey, sometimes crazy has its reasons.

Some farmers think it’s crazy to get out of coffee, some think it’s crazy to stay in. The former are finding ways of navigating the new economics, owning more of the value-chain and earning top dollar. The latter leave because of how hard it is to do coffee correctly. This leaves behind only the most far-sighted and serious of farmers in coffee. So, while volumes are going down across the board, the reasons for this are reasonable. And there’s also reason to expect that qualities from quality areas will to continue to increase as volumes shift to new areas outside of the central highlands.

So it’s reasonable to say that what’s crazy to some, can be incredible to others. Like going to sleep on spooky hill, and waking up to an intensely cold waterfall.

The nice part about meeting over dinner is that I was able to find the farmer who asked the question on price. It was a good discussion, but a side-bar to this narrative. Phrases to highlight include “roasters are not in it for the money” and “your business is in your farm, mine is in my suitcase”. The latter was an attempt to explain how I could afford to travel to visit him, when he could not afford to visit me.